As the headlines and #MeToo hashtag have shown, sexual harassment is pervasive. It’s also multimodal. Street harassment of women pedestrians is common, as documented on HollaBackNYC and Stop Street Harassment. My colleague recently wrote about her experiences of being groped on airplanes. Yes, experiences, plural. There is also evidence of sexual harassment of women bicycling. Amy Lubitow, a sociology professor at Portland State, interviewed cyclists in Portland and found many stories of women being sexually harassed, ranging from frequent catcalls to one incident of men yelling “I wanna grab your ass” from a car driven dangerously close to the woman on her bike. Similar examples are reported in London and cities throughout the U.S. I could not find good quantitative data on sexual harassment and bicycling. One study in Queensland Australia found that men and women cyclists were harassed at the same rate, but it did not analyze sexual harassment rates by gender. Our survey of residents in neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Brooklyn found that 18% of women indicated that being harassed or a victim of crime was a big barrier to bicycling, compared to only 12% of men.

The Washington Post had a piece that focused on harassment on transit that included the statement, “If you’re a woman who rides public transportation, you’re almost guaranteed to experience the kinds of demeaning or threatening encounters that fit squarely within the bounds of the #MeToo conversation.” My worst #MeTooOnTransit experience was on BART, riding home from San Francisco after work over 20 years ago when a man sitting next to me, after several minutes with a newspaper on his lap and hand underneath, with me thinking “he’s not really doing what I think he’s doing, is he?” lifted the paper to expose his penis. My instinct was to flee, escaping from the window seat, past his knees, to the door. It was just before my stop, so without much time to think, I got off and headed home, in shock. In hindsight, I wish I had done something to report him, but it’s hard to think how. At the time, the highest tech thing I had on me was a Walkman; no cell phone to call 911 or take a photo for evidence or identification. Even with many other people on the train, it didn’t cross my mind to speak up or yell, the whole thing was so unbelievable. After getting off the train, what was there to do? The train, and the criminal, were gone. Being the analytical transportation geek that I am, the incident did not change my behavior. I got back on BART the next morning, thinking how such incidents would make some people never use transit again, whether they experienced it directly or just heard my story.

The Post story highlighted the work of Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris from UCLA. She has done several studies on transit crime and harassment, including How to Ease Women’s Fear of Transportation Environments: Case Studies and Best Practices. She and her research team surveyed transit operators throughout the U.S., with 131 agencies responding. This finding was particularly disappointing: “While two-thirds of the respondents (67%) indicated that female passengers have distinct safety and security needs, only about one-third (35%) believed that transit agencies should put into place specific safety and security programs for them” (p. 30). The reasons given for not putting specific programs in place fell into two categories. The first was that the agencies were treating everyone equally, regardless of gender. “The second argument was that women are no more vulnerable than men and do not have special safety and security needs.” Really? I don’t have data on this, but I suspect that more women than men have been exposed to sex organs while on transit.

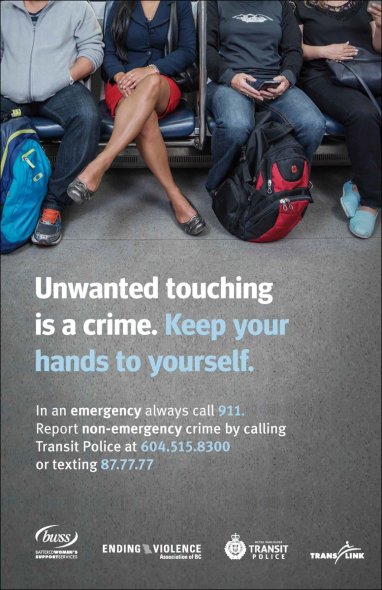

Moreover, at the time of the survey (2006), only three of the 131 agencies had programs in place that distinctly addressed women’s safety and security needs. The report concludes that they found “a serious mismatch between the existing safety and security practices of transit operators and the needs and desires of women passengers” (p. 50). In the Post article, Loukaitou-Sideris encouraged systems for women to report harassment or assault on transit. Some seem to be following that advice. A story linked by the Post described DC Metro’s education efforts, including ads on where to call or text with a complaint. That’s a good start, because the same story stated that that 21% of people surveyed had experienced sexual harassment on public transit in Washington DC. Los Angeles’ Metro launched a campaign called “It’s Off Limits” that includes a 24/7 hotline. A 2015 survey of LA Metro riders found that 21% of train riders and 18% of bus riders had experienced any form of sexual harassment in the past six months, including 10% that had experienced indecent exposure on trains and 7% unwanted touching, groping or fondling. Mexico City’s transit system experimented with an anatomically correct subway seat to highlight the problem of sexual harassment on transit. The photo I used for this post is from an ad on BC Transit in Vancouver Canada. Unfortunately, while some agencies are being proactive, there are still examples, like this, of women reporting about other riders and transit drivers being unhelpful. In her story, the driver replied “You’re a pretty girl, what do you expect?” and several men on Twitter replied with equally or more vile responses.

[…] common on transit. Riffing off that story, Portland State University professor Jennifer Dill writes at her blog about how women are harassed when traveling in public in any way — be it walking, biking, […]

LikeLike

[…] common on transit. Riffing off that story, Portland State University professor Jennifer Dill writes at her blog about how women are harassed when traveling in public in any way — be it walking, biking, riding […]

LikeLike

[…] article was originally posted on Dr. Jennifer Dill’s blog and is a summary of research and experiences of sexual harassment on transit. It’s a follow-up to […]

LikeLike

informative post, well done. harassment is bad, sexual harassment is very bad.

LikeLike

[…] note: This article was originally posted on Dr. Jennifer Dill’s blog and is a summary of research and experiences of sexual harassment on transit. It’s a follow-up to […]

LikeLike